Legal Requirements in Trade Finance and the Basel Framework

As we established previously, prior to 1988, banks primarily regulated themselves. A careful attitude by the management or partners with unlimited liabilities – a legal form that has essentially disappeared apart from some rare banks in places like Switzerland or London – obviated the need for extensive laws and regulations on how to issue loans or credit to private or corporate borrowers.

The industry knew how to manage itself until some lending institutions and banks got themselves into trouble through increasing margin chasing at the expense of stringent loan requirements and management of due-diligence processes.

The first global standard requirements for trade originated from Germany’s largest insolvency after the Second World War, that of the Herstatt Bank in June 1974, an infamous incident which clearly illustrates the issue of settlement risk in international finance.

The Herstatt scandal sent a shiver down the spine of Deutschland AG, the German network of banking and industry, and led to the creation of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), a committee composed of representatives from central banks and regulatory authorities, to help find ways to control risks and address issues caused by systematic flaws and regulatory shortcomings in the future.

The bank was closely tied to the international financial markets, and its collapse triggered an economic downfall that echoed around the world. It prompted global coordination to prevent a recurrence of such disruptions of the credit market.

The coordinated efforts resulted in the Basel I agreement, which established globally applicable requirements and regulations for trade financing.

The financial sector swiftly adapted to these new laws, and sanctions imposed by international regulators forced the committee to react once more. In 1999 the BCBS put in place the second set of regulations – Basel II – to crack down on the amount of fraud and legislative shortcomings in international trade and to address the pitfalls of current trade-financing practices.

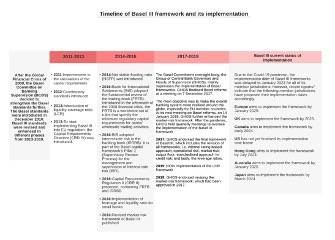

Once it gained momentum, the committee didn’t stop and Basel III was created in response to the 2007-2008 financial crisis, detailing the principles for appropriate risk management and account supervision. The new set of regulations was designed to respond to the overwhelming lack of liquidity buffers in the face of the US housing- market collapse.

In 2017, the committee completed its Basel III post-crisis reforms with the publication of new standards for the calculation of capital requirements for credit risk and credit-valuation adjustment risk.

Many of the lawyers, economists and political participants who developed and calibrated the Basel regulations found their efforts to some extent insufficient as they could not prevent the financial crisis of 2007-08.

The economic crisis unsettled banks and resulted in a severe credit ‘crunch’ and a series of government bailouts of unprecedented scale. After the most urgent crisis management was completed in 2009, the idea of international trade-regulations work was taken up again.

In the wake of this financial crisis, the BCBS published nearly 3,000 pages, covering more than half of the entire regulatory framework. The Basel Framework has reached a whole new dimension. The document today serves as a framework for international trade finance and sets the standard for operations.

There are three categories of legal measures that financial institutions must respect and investors should be aware of: system regulations (large-scale measures across the industry to organise trade in general); prudential regulations (which focus on the institution’s financial health and oblige financial firms to control risk, hold adequate capital, maintain liquidity requirements and monitor large exposure); and non-prudential regulations which are independent of the financial health of the regulated institution.

These regulations include: the permission to lend; transparency regulations; consumer-protection regulations; AML laws; KYC laws; and other consumer-protection regulations.

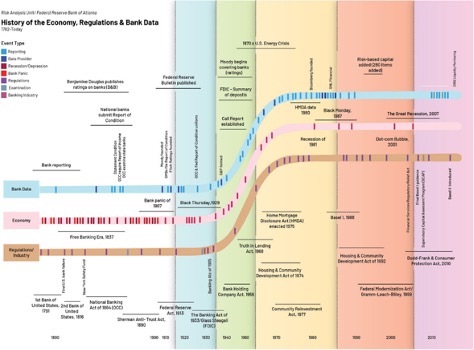

The following diagram outlines the development of the current Basel III framework. The second diagram shows the historical development of US financial regulations in comparison.

¹Bloomberg “Fundamental Review Of The Trading Book (FRTB): Where Do We Stand?”, Bloomberg.com, Last modified 2022 https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/fundamental-review-of-the-trading-book-frtb-where-do-we-stand/.

The above image illustrates the major government regulatory responses to a financial crisis in the history of the US economy. These regulations and laws were put in place to protect the market participants involved in a trade, a particular industry or sector-specific regulations.

Such good intentions of preventive regulations have resulted in a multitude of unintended consequences for SMEs, primarily, making it harder for SMEs to access international trade and finance. To pick just one example, the number of banks providing trade credit in Africa between 2013 and 2019 has declined by 23 percent. In short, large banks like to trade with large corporations. This is the SMEs’ dilemma and the opportunity for companies like Artis and its investors.

The Artis In-House Legal Team

The core task for an internal or external legal team is to review each trade; to prepare, and review transaction documentation; and to ensure compliance with national and international laws, restrictions and other guidelines such as sanctions, which can change with time. Clear transaction structuring and precise drafting is essential.

At this point, our trade is commercial and legally scrutinised. Once a trade is set in motion, various legal questions, not necessarily problems, will keep coming up, often around the quality and the delivery of the product.

If the debtor can prove that there is some sort of defect with the product or its quality – despite having approved the product already – it is the obligation of the factoring client, the borrower, to remedy the situation within a deadline. If the issue is not solved, the invoice is ceded back to the factoring party. Our legal team handles these transactions together with the credit insurer.

A simple example is one where a financing house realised that abiding by international regulations was only one part of the challenge. The investment firm did not realise that the country where they were looking to finance a trade had tariff minimums and stringent import laws.

The country where they intended to do business wouldn’t allow the import of the merchandise in question and wouldn’t allow cargo sizes as large as they had contractually agreed to provide. The result was a costly learning curve. The agency was forced to void the trade entirely.

About the Loss Payee and the Protected Default Clause

The loss payee is the party to whom the claim from a loss is to be paid. Except if otherwise requested and pre-agreed with the investor, Artis only refinances invoices covered by credit insurance or similar. The insurance coverage and the invoice are both assigned to the investors invested in the Artis fund.

The Artis fund and the Artis managed account are the loss payee on record with the credit insurer, protecting the investor from a non-payment situation. Artis’ arrangements include a protected default clause to ensure that all claims are settled within six months regardless of the jurisdiction − worthwhile insurance cover for investors for a swift repayment in case of non-payment by the buyer.

Legal Pitfalls and Investor Coverage

Even with legal mitigants and the appropriate protections in place, the risk of default or insolvency of the buyer remains. In addition to credit insurance, we might seek personal or corporate collateral covering the cost of funding the trade in question, where we only pay out after the product has been accepted by the buyer and the invoice raised. Failure to do so will lead to collection from the insurance company or on the collateral.